Why Voting Rules Matter

Choosing an electoral system is among the most consequential design decisions for a democracy. Voting rules create incentives that shape which candidates are on the ballot, how candidates and their parties behave in campaigns, how much say voters have in the outcome and even who wins, with significant implications for representation, fairness and accountability. In this post, we break down how Plurality, Consensus Choice and Instant Runoff Voting work, and how each design matters. You can also download a pdf version of this explainer.

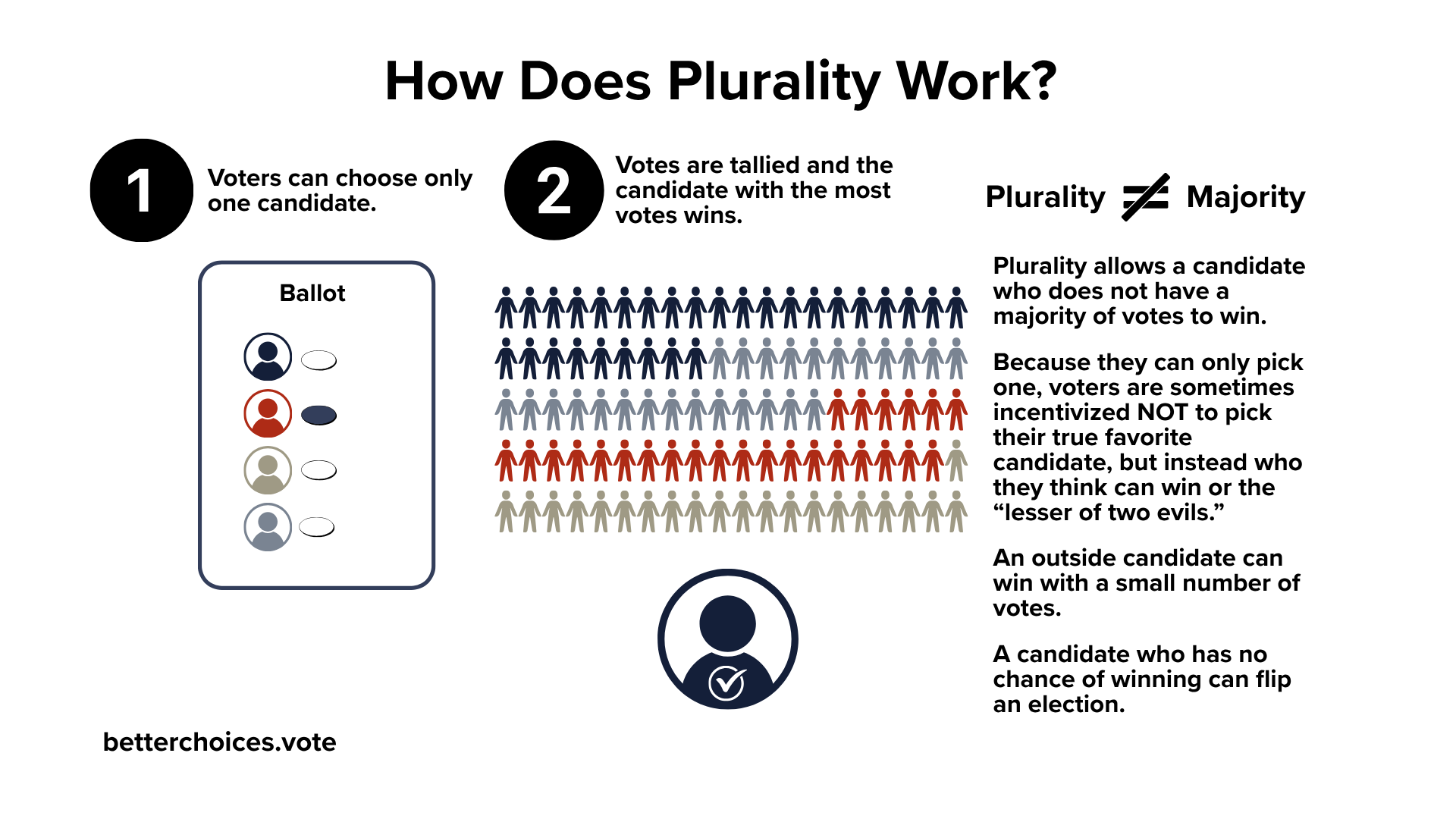

Let’s start with Plurality (also called first-past-the-post, and sometimes referred to as “pick one”) since many elections in the U.S. are decided by plurality voting and partisan primary elections, where voters only express a preference for a single candidate on a ballot.

Under plurality, the candidate with the most first-choice votes wins, even if they don’t have a majority of all votes. When voters can only choose one candidate, closely-contested elections can result in slim margins of victory and result in a winner who does not represent the views of most voters in the electorate.

Partisan primaries followed by plurality-winner general elections are particularly susceptible to partisan extremism. Such systems can lead to elections where voters don’t really have a choice, and the outcomes are essentially predetermined. Candidates have minimal incentive to engage in cross-party coalition-building or outreach to opposing voter groups, often leading to contentious political environments where it’s difficult to productively solve problems and govern.

In elections with districts that lean in one partisan direction, candidates only have to appeal to their partisan base to win. This means that many people do not get a say in the outcome of the election.

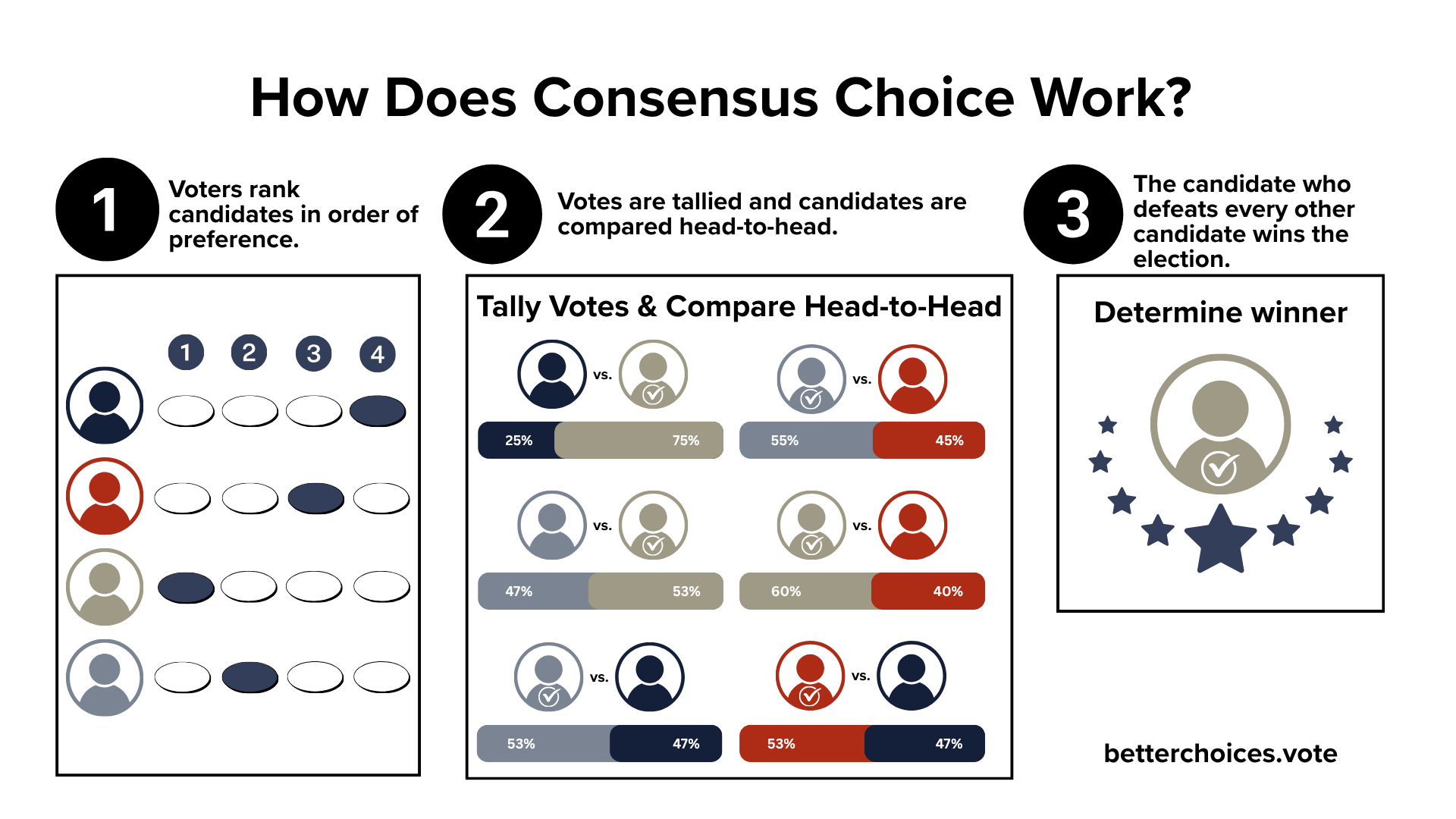

How does Consensus Choice work? First, voters rank candidates in order of preference. Then votes are tallied and candidates are compared head-to-head. The candidate who defeats every other candidate wins the election.

Consensus Choice is one of the most representative and fair ways to determine voter preferences and a winning candidate. Instead of picking just one candidate, voters rank candidates in order of preference (1st, 2nd, 3rd, and so on). Instead of eliminating candidates in rounds as Instant Runoff does, Consensus Choice uses voters’ rankings to determine the winner by comparing candidates head-to-head, much like a round-robin sports tournament. The winning candidate is the candidate who defeats every other candidate head-to-head.

This method seeks to identify the candidate with the broadest support across the electorate. It incentivizes candidates to appeal beyond their core supporters because winning requires showing consistent strength against all competitors, not merely surviving elimination rounds or appealing only to a core base of supporters. That dynamic discourages extremism and division and helps ensure every voter matters.

Under Consensus Choice, every voter’s preference is counted in all candidate comparisons and each voter's full ranking matters equally in every head-to-head matchup, ensuring no individual's voice is disproportionately influential or overlooked. While voters don’t have to rank every candidate, the more candidates they rank, the more say they have in each head-to-head matchup. This ensures their preferences continue to influence the outcome, even if their first choice doesn’t win.

Unlike Instant Runoff, Consensus Choice allows anyone to see and verify how candidates perform against each of the other candidates throughout the ballot counting process. Results can be aggregated and checked without rerunning the entire tally, making it easier for the public to observe the counting process.

How does Instant Runoff Voting work? First, voters rank candidates. Then votes for first choice candidates are tallied. If a candidate has a majority of the votes (more than 50%), there is a winner. If there is no candidate with a majority of votes, a sequential elimination process begins.

Instead of picking just one candidate, under Instant Runoff Voting (also known in the United States as Ranked Choice Voting), voters rank candidates in order of preference (1st, 2nd, 3rd, and so on). In the first round of counting ballots, only first-choice votes are counted. If no candidate has a majority (>50%), the candidate with the fewest first-choice votes is eliminated, and votes for that candidate are transferred to the voters’ next-ranked candidates. This process repeats until one candidate receives a majority of the remaining votes.

Because it eliminates candidates one at a time, Instant Runoff may eliminate a candidate early who would have broader appeal overall. In addition, the elimination order gives small, organized groups asymmetric leverage to tip the outcome of an election.

Under IRV, if a voter does not rank every candidate on the ballot, their ballot is set aside and no longer counts toward the final outcome after their ranked candidates are eliminated.

Since IRV involves multiple rounds of elimination, the final winner may not be determined until all eligible ballots have been cast and processed. It can also be harder for voters to follow the results as they unfold due to the sequential elimination process. Results can be audited, but not every jurisdiction allows for adding up local results into a complete tally without re-running the elimination process.

This is an illustration we created for an example Professor Eric Maskin, a Nobel Laureate in Economic Science, shared with the audience at Texas Tribune’s 2025 TribFest. Note that each method produces a different winner from an electorate with the same preferences. It demonstrates why Consensus Choice is the electoral method best suited for identifying a candidate whom a majority of voters prefer over each other candidate in an election. Because it uses sequential elimination, Instant Runoff Voting ignores many voters’ second choice preferences and can eliminate early a candidate who would have been majority preferred over others in a head-to-head matchup. But plurality is even worse because it doesn’t even give voters a second choice, meaning that 60% of this electorate didn’t get a chance to express their preferences about a winning candidate.